Cognitive behavioral therapy can teach patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) information-processing skills that address the biological roots of their gastrointenstinal symptoms, new research shows for the first time. The findings raise the possibility that CBT-responsive IBS patients can be identified in clinical practice using microbial biomarkers, before less effective treatments are initiated at great expense to the patient and health care system.

This work demonstrates that teaching people how to think more flexibly in specific situations can reduce the physical tension and stress that can disrupt brain-gut interactions and crank up symptoms,

said Jeffrey M. Lackner, PsyD, co-senior author of the paper1. He is professor in the Department of Medicine and chief of the Division of Behavioral Medicine in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at University at Buffalo.

Role Of The Microbiome

The study shows how a non-drug, non-dietary treatment for IBS induces changes in brain function and in the microbiome by normalizing ways of processing information, Lackner explained.

Emeran A. Mayer, MD, an internationally known expert on the interactions between the digestive and nervous systems, is co-senior author on the paper. He is a professor in the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and executive director of the G. Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience.

Dr. Lackner’s collaborative project with UCLA is an important breakthrough in the understanding of how cognitive behavioral therapy can alter brain-gut interaction to provide relief for IBS patients. This study’s translational research provides new hope for those afflicted with this debilitating disease,

said Allison Brashear, MD, UB’s vice president for health sciences and dean of the Jacobs School.

Randomized Clinical Trial

Eighty-four IBS patients were recruited from the parent CBT trial – the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Outcome Study, a National Institutes of Health-funded clinical trial led by Lackner that has transformed the way IBS is understood and treated.

The 84 participants underwent neuroimaging and detailed clinical assessment at clinical sites at UB and Northwestern University. UB also collected microbiome data through fecal sampling from 34 of the patients.

Eligible patients were randomized to receive 10 sessions of clinic-based cognitive behavioral therapy or four sessions of largely home-based CBT with minimal therapist contact over a 10-week acute phase. Both treatments were developed at UB.

The trial was unusually complex as the researchers collected symptom data across different sites before and after treatment. University at Buffalo developed the treatment, delivered it and collected data, while UCLA analyzed gut microbiome and neuroimaging data.

Responders And Non-responders

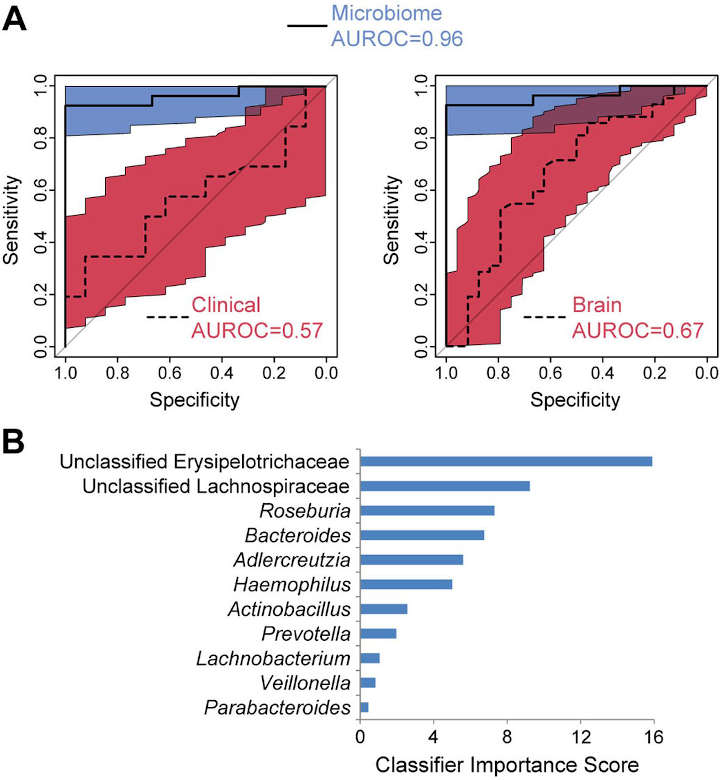

Of the 84 participants in the trial, 58 were classified as CBT responders and 26 were classified as non-responders. While there were small pre-treatment differences between brain network connectivity for responders and non-responders, the significant difference was how much the connectivity changed after treatment.

Responders showed greater baseline connectivity than non-responders between the central autonomic network and the emotional regulation network, according to the study.

The pattern of data may explain normal versus abnormal gut function and just how the brain-gut can influence symptoms and the relief of them. Larger studies are needed to characterize the functional correlates of gut microbial changes and to identify distinct subtypes of IBS patients for whom brain- and gut-directed therapies are most effective,

Lackner said.

Because of the lack of reliable biomarkers capable of IBS classification, symptom improvement and efficacy of treatment currently are typically assessed by patient-reported measures2.

Wider studies are needed to determine the functional correlates of gut microbial changes and to identify distinct subtypes of IBS patients for whom brain- and gut-directed therapies are most effective, the authors write.

- Jonathan P. Jacobs et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome induces bidirectional alterations in the brain-gut-microbiome axis associated with gastrointestinal symptom improvement. Microbiome 9, 236 (2021). ↩︎

- Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997; 11(2):395–402. ↩︎

Last Updated on October 1, 2022